If ever there were a candidate for “Most Hyped Technology” during the late 90s and 2000s, it was XML (though Java would be a close contender for the title). In this article I’ll explain exactly what XML is and what is used for.

XML was created because HTML is specifically designed to describe documents for display in a Web browser, and not much else. It becomes cumbersome if you want to display documents in a mobile device or do anything that’s even slightly complicated, such as translating the content from German to English. HTML’s sole purpose is to allow anyone to quickly create Web documents that can be shared with other people. XML, on the other hand, isn’t just suited to the Web – it can be used in a variety of different contexts, some of which may not have anything to do with humans interacting with content (for example, Web Services use XML to send requests and responses back and forth). HTML rarely (if ever) provides information about how the document is structured or what it means. In layman’s terms, HTML is a presentation language, whereas XML is a data-description language. For example, if you were to go to any ecommerce Website and download a product listing, you’d probably get something like this:

ABC Products ABC Products

Product One

Product One is an exciting new widget that will simplify your life.

Cost: $19.95

Shipping: $2.95

Product Two

. Product Three

Cost: $24.95

This is such a terrific widget that you will most certainly want to buy one for your home and another one for your office!

. Product One Product One is an exciting new widget that will simplify your life. $19.95 $2.95 Product Two .Product Three This is such a terrific widget that you will most certainly want to buy one for your home and another one for your office! $24.95 $0.00 Notice that this new document contains absolutely no information about display. What does a

From the casual observer’s viewpoint, a given XML document, such as the one we saw in the previous section, appears to be no more than a bunch of tags and letters. But there’s more to it than that! Let’s consider our XML example from a structural standpoint. No, not the kind of structure we bring to a document by marking it up with XML tags; let’s look at this example on a more granular level. I want to examine the contents of a typical XML file, character by character. The simplest XML elements contain an opening tag, a closing tag, and some content. The opening tag begins with a left angle bracket ( < ), followed by an element name that contains letters and numbers (but no spaces), and finishes with a right angle bracket ( >). In XML, content is usually parsed character data. It could consist of plain text, other XML elements, and more exotic things like XML entities, comments, and processing instructions (all of which we’ll see later). Following the content is the closing tag, which exhibits the same spelling and capitalization as your opening tag, but with one tiny change: a / appears right before the element name. Here are a few examples of valid XML elements:

some content here one two Also, if you nest your elements improperly (i.e. close an element before closing another element that is inside it), your document won’t be valid. (I know I keep mentioning validity – we’ll talk about it in detail soon!) For example, Web browsers don’t generally complain about the following:

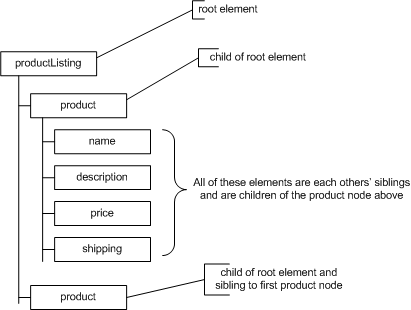

Some text that is bolded, some that is italicized.In XML, this improper nesting of elements would cause the program reading the document to raise an error. As XML allows you to create any language you want, the inventors of XML had to institute a special rule, which happens to be closely related to the proper nesting rule. The rule states that each XML document must contain a single root element in which all the document’s other elements are contained. As we’ll see later, almost every single piece of XML development you’ll do is facilitated by this one simple rule.

Did you notice the tag. What information should be contained in an attribute? What should appear between the tags of an element? This is a subject of much debate, but don’t worry, there really are no wrong answers here. Remember: you’re the one defining your own language. Some developers (including me!) apply this rule of thumb: use attributes to store data that doesn’t necessarily need to be displayed to a user of the information. Another common rule of thumb is to consider the length of the data. Potentially large data should be placed inside a tag; shorter data can be placed in an attribute. Typically, attributes are used to “embellish” the data contained within the tag. Let’s examine this issue a little more closely. Let’s say that you wanted to create an XML document to keep track of your DVD collection. Here’s a short snippet of the code you might use:

1 Raiders of the Lost Ark 1981 Steven Spielberg Harrison Ford Karen Allen John Rhys-Davies It’s unlikely that anyone who reads this document would need to know the ID of any of the DVDs in your collection. So, we could safely store the ID as an attribute of the

In other parts of our DVD listing, the information seems a little bare. For instance, we’re only displaying an actor’s name between the

Harrison Ford In this case, though, I’d probably revert to our rule of thumb – most users would probably want to know at least some of this information. So, let’s convert some of these attributes to elements:

Harrison Ford male 50 Beware of Redundant Data From a completely different perspective, one could argue that you shouldn’t have all this repetitive information in your XML file. For example, your collection’s bound to include at least one other movie that stars Harrison Ford. It would be smarter, from an architectural point of view, to have a separate listing of actors with unique IDs to which you could link. Empty-Element Tags Some XML elements are said to be empty – they contain no content whatsoever. Familiar examples are the img and br elements in HTML. In the case of img , for example, all the element’s information is contained in its tag’s attributes. The

tag, on the other hand, does not normally contain any attributes – it just signifies a line break. Remember that in XML all opening tags must be matched by a closing tag. For empty elements, you can use a single empty-element tag to replace this:

The / at the end of this tag basically tells the parser that the element starts and ends right here. It’s an efficient shorthand method that you can use to mark up empty elements quickly. The XML Declaration The line right at the top of our example is called the XML declaration:

It’s not strictly necessary to include this line, but it’s the best way to make sure that any device that reads the document will know that it’s an XML document, and to which version of XML it conforms. Entities I mentioned entities earlier. An entity is a handy construct that, at its simplest, allows you to define special characters for insertion into your documents. If you’ve worked with HTML, you know that the < entity inserts a literal < character into a document. You can’t use the actual character because it would be treated as the start of a tag, so you replace it with the appropriate entity instead. XML, true to its extensible nature, allows you to create your own entities. Let’s say that your company’s copyright notice has to go on every single document. Instead of typing this notice over and over again, you could create an entity reference called copyright_notice with the proper text, then use it in your XML documents as ©right_notice; . What a time-saver! We’ll cover entities in more detail later on. More than Structure… XML documents are more then just a sequence of elements. If you take another, closer look at our product or DVD listing examples, you’ll notice two things:

Earlier in this article, I made a point about XML allowing you to separate information from presentation. I also mentioned that you could use other technologies, like CSS (Cascading Style Sheets) and XSLT (Extensible Stylesheet Language Transformations), to make the information display in different contexts. Note: Notice that in XSLT, it’s “stylesheet,” but in CSS it’s “style sheet”! Because we’ve taken the time to create XML documents, our information is no longer locked up inside proprietary formats such as word processors or spreadsheets. Furthermore, it no longer has to be “re-created” every time you want to create alternate displays of that information: all you have to do is create a style sheet or transformation to make your XML presentable in a given medium. For example, if you stored your information in a word processing program, it would contain all kinds of information about the way it should appear on the printed page – lots of bolding, font sizes, and tables. Unfortunately, if that document also had to be posted to the Web as an HTML document, someone would have to convert it (either manually or via software), clean it up, and test it. Then, if someone else made changes to the original document, those changes wouldn’t cascade to the HTML version. If yet another person wanted to take the same information and use it in a slide presentation, they might run the risk of using outdated information from the HTML version. Even if they did get the right information into their presentation, you’d still need to track three locations in which your information lived. As you can see, it can get pretty messy! Now, if the same information were stored in XML, you could create three different XSLT files to transform the XML into HTML, a slide presentation, and a printer-friendly file format such as PostScript. If you made changes to the XML file, the other files would also change automatically once you passed the XML file through the process. (This notion, by the way, is an essential component of single-sourcing – i.e. having a “single source” for any given information that’s reused in another application.) As you can see, separating information from presentation makes your XML documents reusable, and can save hassles and headaches in environments in which a lot of information needs to be stored, processed, handled, and exchanged.

Now we’re going to dig a little deeper into XML as we talk about namespaces, XHTML, XSLT, and CSS. I’d like to zoom out a little and introduce you to some of the wacky siblings that make up the XML “Family of Technologies.” Although I’m going to list a number of tools and technologies here, we’ll cover only a few in this article.

XSLT stands for Extensible Stylesheet Language Transformations. It is both a style sheet specification and a kind of programming language that allows you to transform an XML document into the format of your choice: stripped ASCII text, HTML, RTF, and even other dialects of XML.

XPath is a language for locating and processing nodes in an XML document. Because each XML document is, by definition, a hierarchical structure, it becomes possible to navigate this structure in a logical, formal way (i.e. by following a path).

A document type definition (DTD) is a set of rules that governs the order in which your elements can be used, and the kind of information each can contain. XML Schema is a newer standard with capabilities that extend far beyond those of DTDs. While a DTD can provide only general control over element ordering and containment, schemas are a lot more specific. They can, for example, allow elements to appear only a certain number of times, or require that elements contain specific types of data such as dates and numbers. Both technologies allow you to set rules for the contents of your XML documents. If you need to share your XML documents with another group, or you must rely on receiving well-formed XML from someone else, these technologies can help ensure that your particular set of rules is properly followed.

The ability of XML to allow you to define your own elements provides flexibility and scope. But it also creates the strong possibility that, when combining XML content from different sources, you’ll experience clashes between code in which the same element names serve very different purposes. For example, if you’re running a bookstore, your use of

XHTML stands for Extensible Hypertext Markup Language. Technically speaking, it’s a reformulation of HTML 4.01 as an application of XML, and is not part of the XML family of technologies. To save your brain from complete meltdown, it might be simplest to think of XHTML as a standard for HTML markup tags that follow all the well-formedness rules of XML we covered earlier. What’s the point of that, you might ask? Well, there are tons and tons and tons of Websites out there that already use HTML. No one in their right mind could reasonably expect them all to switch to XML overnight. But we can expect that some of these pages – and a large percentage of the new pages that are being coded as you read this – will make the transition thanks to XHTML. As you can see, the XML family of technologies is a pretty big group – those XML family reunions are undoubtedly interesting! It’s also important to note that these technologies are open standards-based, which means that any new XML technologies (or proposed changes to existing ones) must follow a public process set down by the W3C (the World Wide Web Consortium) in order to gain acceptance in the community. Although this means that some ideas take quite a while to reach fruition, and tend to be built by committee, it also means that no single vendor is in total control of XML. And this, as Martha Stewart might say, is a good thing.

My example Hello

Believe it or not, that snippet will render without a problem in most Web browsers. And so will this:

Hello

HelloThis is a sentence.

There are three XHTML DOCTYPES: Strict Use this with CSS to minimize presentational clutter. In fact, the Strict DOCTYPE expressly prohibits the use of HTML’s presentation tags.

Transitional Use this to take advantage of HTML’s presentational features and/or when you’re supporting non-CSS browsers.

Frameset Use this when you want to use frames to partition the screen. A Minimalist XHTML Example Here’s a very simple document that illustrates the rules above: A very simple XHTML document a simple paragraph that contains a properly formatted

break and some properly nested formatting.

That’s more than enough information about XHTML for the moment. Let’s move on to discuss namespaces and XSLT.

XML Namespaces were invented to rectify a common problem: the collision of documents using identical element names for different data. Let’s revisit our namespace example from the introduction. Imagine you were running a bookstore and had an inventory file (called inventory.xml , naturally), in which you used a title element to store book titles. Let’s also say that – unlikely though it sounds – your XML document becomes mixed in with a mortgage broker’s master record file. In this file, the mortgage broker has used title to store information about a property’s legal title. A human being could probably figure out that one title has nothing to do with the other, but an application that tried to sort it out would go nuts. We need to have a way to distinguish between the two different semantic universes in which these identical terms exist. Let’s get even more ambiguous: imagine you had an inventory.xml file in your bookstore that used the title element to store book titles, and a separate sales.xml file that used the title element to store the same information, but in a completely different context. Your inventory file stores information about books on the shelf, but the sales file stores information about books that have been bought by customers. In either situation, regardless of the chasm that lies between the contexts of these identical terms, we need a way to properly label each context. Namespaces to the rescue! XML namespaces allow you to create a unique namespace based on a URI (Uniform Resource Identifier), give that namespace a prefix, and apply that prefix to XML document elements.

To use and declare a namespace, we must first tie the namespace to a URI. Notice that I didn’t say URL – a specific location that you can reach (although a URI can be a URL). A URI is simply a unique identifier that distinguishes one thing (say, an XML document standard) from another. URIs can take the following forms:

Uniform Resource Locator: a specific protocol, machine address, and file path (e.g. http://www.tripledogdaremedia.com/index.php ).

Uniform Resource Name: a persistent name that doesn’t point to an actual location for the resource, but still identifies it uniquely. For example, all published books have an ISBN. The ISBN uniquely identifies the book, but nowhere in the ISBN is there any indication as to which shelf it sits on in any particular bookstore. However, armed with the ISBN, you could walk into the store, ask an employee to search for you, and they could take you right to the book (provided, of course, that it was in stock. The following are examples of good URIs:

http://www.tripledogdaremedia.com/XML/Namespaces/1 urn:bookstore-inventory-namespaceWe want to use our namespace throughout our XML documents, though, and the last thing we want to do is type out an entire URI every time we need to distinguish one context from another. So, we define a prefix to represent our namespace to ease the strain on our typing fingers:

inv="urn:bookstore-inventory-namespace"But, wait – we’re not done yet! We need a way to tell the XML parser that we’re creating a namespace. The agreed way to do that is to prefix the namespace declaration with xmlns :, like this:

xmlns:inv="urn:bookstore-inventory-namespace"At this point, we have something useful. If we needed to, we could add our prefix to appropriate elements to disambiguate (I love that term!) any potentially ambiguous usage, like this:

Build Your Own XML-Powered Web Site Title Deed to the house on 123 Main St., YourTown Namespaces make it very clear that

In most cases, placing your namespace declarations will be rather easy. They’re commonly located in the root element of a document, like so:

Please note, however, that namespaces have scope. Namespaces affect the element in which they are declared, as well as all the child elements of that element. In fact, as you’ll see when we discuss XSLT later, we’ll use the xsl prefix in the very element in which we define the XSL namespace:

Any namespace declaration that’s placed in a document’s root element becomes available to all elements in that document. However, if you want to limit your namespace scope to a certain part of a document, feel free to do so – remembering, of course, that this can get pretty tricky. My advice is to declare your namespaces in the document’s root element, then use the prefixes when you need them.

It would become pretty tiresome to have to type a prefix for every single element in a document. Fortunately, you can declare a default namespace that doesn’t contain a prefix. This namespace will apply to all elements that don’t contain prefixes. Let’s take another look at a typical opening

In an XSLT file, this namespace governs all elements that aren’t specifically prefixed as XSLT elements, identifying them as XHTML tags. On the other side of the coin, all XSLT elements must be given the xsl: prefix.

Let’s get started with XSLT. For our first exercise, we’ll reuse the very simple Letter to Mother example we saw in the CSS section. We’ll also create a very basic Extensible Stylesheet Language (XSL) file to transform that XML. Keeping both these elements simple will give us the opportunity to step through the major concepts involved. First, let’s create the XSL file. This file will contain all the instructions we’ll need in order to transform the XML elements into raw text. In what will become a recurring theme in the world of XML, XSL files are in fact XML files in their own right. They must therefore follow the rules that apply to all XML documents: an XSL file must contain a root element, all attribute values must be quoted, and so on. All XSL documents begin with a stylesheet element This element contains information that the XSLT processor needs to do its job: Example 2.4. letter2text.xsl (excerpt)

The version attribute is required. In most cases, you’d use 1.0 , as this is the most widely supported version at the time of this writing. The xmlns:xsl attribute is used to declare an XML namespace with the prefix xsl . For your stylesheet transformation to work at all, you must declare an XML namespace for the URI https://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform in your opening

Other possible values for the method attribute include html and xml , but we’ll cover those a little later. Now we come to the heart of XSLT – the template and apply-templates elements. Together, these two elements make the transformations happen. Put simply, the XSLT processor (for our immediate purposes, the browser) starts reading the input document, looking for elements that match any of the template elements in our style sheet. When one is found, the contents of the corresponding template element tells the processor what to output before continuing its search. Where a template contains an apply-templates element, the XSLT processor will search for XML elements contained within the current element and apply templates associated with them. There are some exceptions and additional complications that we’ll see as we move forward, but for now, that’s really all there is to it. The first thing we want to do is match the letter element that contains the rest of our document. This is fairly straightforward: Example 2.6. letter2text.xsl (excerpt)

TO: FROM: MESSAGE: While the logic of this style sheet is complete and correct, there’s a slight formatting issue left to be tackled. Left this way, the output would look something like this:

TO: Mom FROM: Tom MESSAGE: Happy Mother's DayThere’s an extraneous line break at the top of the file, and each of the lines begins with some unwanted whitespace. The line break and whitespace is actually coming from the way we’ve formatted the code in the style sheet. Each of our three main templates begins with a line break and then some whitespace before the label, which is being carried through to the output. But wait – what about the line break and whitespace that ends each template? Why isn’t that getting carried through to the output? Well by default, the XSLT standard mandates that whenever there in only whitespace (including line breaks) between two tags, the whitespace should be ignored. But when there is text between two tags (e.g. TO: ), then the whitespace in and around that text should be passed along to the output. Avoid Whitespace Insanity The vast majority of XML books and tutorials out there completely ignore these whitespace treatment issues. And while it’s true that whitespace doesn’t matter a lot of the time when you’re dealing exclusively with XML documents (as opposed to formatted text output), it’s likely to sneak up on you and bite you in the butt eventually. Best to get a good grasp of it now, rather than waiting for insanity to set in when you least expect it. The tag is useful for controlling the effects of whitespace in our style sheets. All it does is output the text it contains, even if it is just whitespace. Here’s the adjusted version of our style sheet, with tags used to isolate text we want to output: Example 2.9. letter2text.xsl

xsl:text>TO: /xsl:text> xsl:text> /xsl:text> xsl:text>FROM: /xsl:text> xsl:text> /xsl:text> xsl:text>MESSAGE: /xsl:text> xsl:text> /xsl:text> Notice how each template now outputs its label (e.g. TO: ) followed by a single space, then finishes off with a line break. All the other whitespace in the style sheet is ignored, since it isn’t mixed with text. This gives us the fine control over formatting that we need when outputting a plain text file. Are we done yet? Not quite. We have to go back and add to our XML document a style sheet declaration that will point to our XSL file, just like we did for the CSS example. Simply open the XML document and insert the following line before the opening element: Example 2.10. letter-text.xml (excerpt)

Now, our XML document looks like this: Example 2.11. letter-text.xml Mom Tom Happy Mother's Day

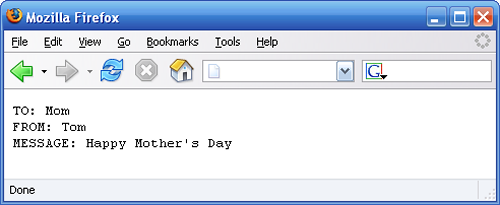

When you view the XML document in your browser, you should see something similar to the result pictured in Figure 2.2, “Viewing XSL results in Firefox.”. You can try viewing this in Internet Explorer as well, but you won’t see the careful text formatting we applied in our style sheet. Internet Explorer interprets the result as HTML code, even when the style sheet clearly specifies that it will output text. As a result, whitespace is collapsed and our whole document appears on one line. Figure 2.2. Viewing XSL results in Firefox. If you’re curious, go ahead and view the source of this document. You’ll notice that you won’t see the output of the transformation (technically referred to as the result tree), but you can see the XML document source.

That wasn’t so bad, was it? You successfully transformed a simple XML document into flat ASCII text, and even added a few extra tidbits to the output. Now, it’s time to make things a little more complex. Let’s transform the XML document into HTML. Here’s the great part – you won’t have to touch the original XML document (aside from pointing it at a new style sheet, that is). All you’ll need to do is create a new XSL file: Example 2.12. letter2html.xsl

xsl:output method="html"/> html> head>title>Letter/title>/head> body>/body> /html> b>TO: /b>br/> b>FROM: /b>br/> b>MESSAGE: /b>br/>

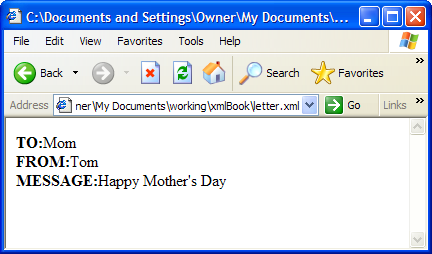

Right away, you’ll notice that the style sheet’s output element now specifies an output method of html . Additionally, our first template now outputs the basic tags to produce the framework of an HTML document, and doesn’t bother suppressing the whitespace in the source document with a select attribute. Other than that, these instructions don’t differ much from our text-only style sheet. In fact, the only other changes we’ve made have been to tag the label for each line to be bold, and end each line with an HTML line break (

). We no longer need the tags, since our HTML and

tags perform the same function. Note the space following each label, which is inside the tag so that it won’t be ignored by the processor. All we have to do now is edit our XML file to make sure that the instruction references our new style sheet ( letter-html.xml in the code archive), and we’re ready to display the results in a Web browser. You should see something similar to Figure 2.3, “Viewing XSL Results in Internet Explorer.”. Figure 2.3. Viewing XSL Results in Internet Explorer. Using XSLT to Transform XML into other XML What happens if you need to transform your own XML document into an XML document that meets the needs of another organization or person? For instance, what if our letter document, which uses , , and tags inside a tag, needed to have different names, say , , and ? Not to worry – XSLT will save the day! And, as with the two previous examples, we don’t even need to worry about changing the source XML document. All we have to do is create a new XSL file, and we’re set. As before, we’ll open with the standard stylesheet element, but, this time, we’ll choose xml as our output method. We’re also going to instruct XSLT to indent the resulting XML: Example 2.13. letter2xml.xsl (excerpt)

The elements are structured as before, but this time they output the new XML elements: Example 2.14. letter2xml.xsl (excerpt)

Here we have declared a default namespace for tags without prefixes in the style sheet. Thus tags like and will be correctly identified as XHTML tags. Next up, we can flesh out the output element to more fully describe the output document type: Example 2.16. letter2xhtml.xsl (excerpt) In addition to the method and indent

attributes, we have specified a number of new attributes here: omit-xml-declaration This tells the processor not to add a declaration to the top of the output document. Internet Explorer for Windows displays XHTML documents in Quirks Mode when this declaration is present, so by omitting it we can ensure that this browser will display it in the more desirable Standards Compliance mode. media-type Though not required by current browsers, setting this attribute to application/xhtml+xml offers another way for the browser to identify the output as an XHTML document, rather than plain XML. encoding Sets the character encoding of the output document, controlling which characters are escaped as character references ( &xnn; ). doctype-public, doctype-system Together, these two attributes provide the values needed to generate the DOCTYPE declaration for the output document. In this example, we’ve specified values for an XHTML 1.0 Transitional document, but you could also specify an XHTML 1.0 Strict document if that’s what you need: doctype-public doctype-system= "https://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml1/DTD/xhtml1-strict.dtd"/> The rest of the style sheet is as it was for the HTML output example we saw above. Here’s the complete style sheet so you don’t have to go searching: Example 2.17. letter2xhtml.xsl

Letter TO:

FROM:

MESSAGE:

Point the processing instruction in your XML document at this style sheet and then load it in Firefox or Internet Explorer. You should see the output displayed as an XHTML document. So yes, if the XML you are generating happens to be XHTML, a browser can display it just fine. Otherwise, what we need to display XML output is some kind of standalone XSLT processor that we can run instead of a Web browser.

So far, we’ve created some very simple XML documents and learned what they’re made of. We’ve also walked through some very simple examples in which we’ve transformed XML into something else, be it text, HTML, or different XML. Now, it’s time to learn how to make your XML documents consistent.

Ralph Waldo Emerson, the great American thinker and essayist, once said, “A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.” Well, foolish or not, in the world of XML, we like consistency. In fact, in many contexts, consistency can be a very beautiful thing. However, there will come a time when you need your XML document to follow some rules – to pass a validity test – and those times will require that your XML data be consistently formatted. For example, our CMS should not allow a piece of data that’s supposed to be in the admin information file to show up in a content file. What we need is a way to enforce that kind of rule. In XML, there are two ways to set up consistency rules: DTDs and XML Schema. A DTD (document type definition) is a tried and true (if not old-fashioned) way of achieving consistency. It has a peculiar, non-XML syntax that many XML newcomers find rather limiting, but which evokes a comfortable, hometown charm among the old-school XML programmers. XML Schema is newer, faster, better, and so on; it does a lot more, and is written like any other XML document, but many find it just as esoteric as DTDs. Information on DTDs and XML Schema could fill thick volumes if we gave it a chance. Each of these technologies contains lots of hidden nooks and crannies crammed with rules, exceptions, notations, and side stories. But, remember why we’re here: we must learn as much as we need to know, then apply that knowledge as we build an XML-powered Website.

Speaking of side stories, did you know that DTD actually stands for two things? It stands not just for document type definition, but also document type declaration. The declaration consists of the lines of code that make up the definition. Since the distinction is a tenuous one, we’ll just call them both “DTD” and move on! This section will focus on DTDs, as you’re still a beginner, and providing information on XML Schema would be overkill. However, I will take a few minutes to explain XML Schema at a high level, and provide some comparisons with DTDs. Just a warning before we start: consistency in XML is probably the hardest aspect we’ve covered so far, because DTDs can be pretty esoteric things. However, I think you’ll find it worth your while, since using a DTD will prevent many problems down the road.

The way DTDs work is relatively simple. If you supply a DTD along with your XML file, then the XML parser will compare the content of the document with the rules that are set out in the DTD. If the document doesn’t conform to the rules specified by the DTD, the parser raises an error and indicates where the processing failed. DTDs are such strange creatures that the best way to describe them is to just jump right in and start writing them, so that’s exactly what we’re going to do. A DTD might look something like this:

ELEMENT letter (to,from,message)

This is called an element declaration. You can declare elements in any order you want, but they must all be declared in the DTD. To keep things simple, though, and to mirror the order in which elements appear in the actual XML file, I’d suggest that you do what we’ve done here: declare your root element first. A DTD element declaration consists of a tag name and a definition in parentheses. These parentheses can contain rules for any of:

ELEMENT to (#PCDATA) ELEMENT from (#PCDATA) ELEMENT message (#PCDATA)Here, we see #PCDATA used to define the contents of our elements. #PCDATA stands for parsed character data, and refers to anything other than XML elements. So whenever you see this notation in a DTD, you know that the element must contain only text. Mixed Content What if you want to have something like this in your XML document?

This is a paragraph in which items are bolded, italicized, and even underlined. Some items are even deemed high priority . You’d probably think that you needed to declare the paragraph element as containing a sequence of #PCDATA and other elements, like this:

ELEMENT paragraph (#PCDATA,b,i,u,highpriority)

You might think that, but you’d be wrong! The proper way to declare that an element can contain mixed content is to separate its elements using the | symbol and add a * at the end of the element declaration:

ELEMENT paragraph (#PCDATA|b|i|u|highpriority)*

This notation allows the paragraph element to contain any combination of plain text and b , i , u , and highpriority elements. Note that with mixed content like this, you have no control over the number or order of the elements that are used. Empty Elements What about elements such as the hr and br , which in HTML contain no content at all? These are called empty elements, and are declared in a DTD as follows:

ELEMENT hr EMPTY ELEMENT br EMPTYSo far, most of this makes good sense. Let’s talk about attribute declarations next. Attribute Declarations Remember attributes? They’re the extra bits of information that hang around inside the opening tags of XML elements. Fortunately, attributes can be controlled by DTDs, using what’s called an attribute declaration. An attribute declaration is structured differently than an element declaration. For one thing, we define it with !ATTLIST instead of |!ELEMENT . Also, we must include in the declaration the name of the element that contains the attribute(s), followed by a list of the attributes and their possible values. For example, let’s say we had an XML element that contained a number of attributes:

Harrison Ford ELEMENT actor (#PCDATA) ATTLIST actor actorid ID #REQUIRED gender (male|female) #REQUIRED type CDATA #IMPLIEDENTITY copyright "© 2004 by Triple Dog Dare Media"ENTITY % acceptable "(#PCDATA|b|i|u|citation|dialog)*" ELEMENT paragraph %acceptable; ELEMENT intro %acceptable; ELEMENT sidebar %acceptable; ELEMENT note %acceptable;What this says is that each of the elements paragraph , intro , sidebar , and note can contain regular text as well as b , i , u , citation , and dialog elements. Not only does the use of a parameter entity reduce typing, it also simplifies maintenance of the DTD. If, in the future, you wanted to add another element ( sidebar ) as an acceptable child of those elements, you’d only have to update the %acceptable; entity:

ENTITY % acceptable "(#PCDATA|b|i|u|citation|dialog|sidebar)"External entities point to external information that can be copied into your XML document at runtime. For example, you could include a stock ticker, inventory list, or other file, using an external entity.

ENTITY favquotes SYSTEM "http://www.example.com/favstocks.xml"In this case, we’re using the SYSTEM keyword to indicate that the entity is really a file that resides on a server. You’d use the entity in your XML documents as follows:

Current Favorite Stock Picks &favquotes;External DTDs The DTD example we saw at the start of this section appeared within the DOCTYPE declaration at the top of the XML document. This is okay for experimentation purposes, but with many projects, you’ll likely have dozens – or even hundreds – of files that must conform to the same DTD. In these cases, it’s much smarter to put the DTD in a separate file, then reference it from your XML documents. An external DTD is usually a file with a file extension of .dtd – for example, letter.dtd . This external DTD contains the same notational rules set forth for an internal DTD. To reference this external DTD, you need to add two things to your XML document. First, you must edit the XML declaration to include the attribute standalone="no" :

This tells a validating parser to validate the XML document against a separate DTD file. You must then add a DOCTYPE declaration that points to the external DTD, like this:

This will search for the letter.dtd file in the same directory as the XML file. If the DTD lives on a Web server, you might point to that instead:

XML and HTML are both markup languages, but they serve different purposes. HTML is used to display data and focuses on how data looks. It has predefined tags that are used to format and display information on a web page. On the other hand, XML is used to store and transport data. It doesn’t do anything on its own, but provides a way to structure data so that it can be read by different types of applications. XML tags are not predefined; you must define your own tags.

XML is widely used in web services, which are applications that can be published and called over the Internet by client applications. XML provides a way to encode data in a format that can be read by these client applications, regardless of how the application was created or what platform it runs on. This makes it a key technology for enabling interoperability between disparate systems.

XML namespaces are a mechanism for avoiding name conflicts in XML documents. They work similarly to the file directories on your computer, allowing you to distinguish between elements and attributes that have the same name but belong to different libraries. An XML namespace is declared using the xmlns attribute in the start tag of an element.

An XML schema is a description of the structure of an XML document. It defines the elements and attributes that can appear in a document, the types of data that can be stored in elements and attributes, and the order in which elements can appear. XML schemas are used to validate XML documents, ensuring that they meet the requirements specified in the schema.

Unlike HTML, XML supports data types. This means that you can specify the type of data that an element or attribute can contain, such as integer, string, date, etc. This is done using an XML schema. When an XML document is validated against a schema, the validator checks that the data in the document matches the data types specified in the schema.

An XML parser is a software library or package that provides interfaces for client applications to work with XML documents. It reads XML documents and provides an interface for programs to access their content and structure. Parsers check for well-formedness: whether the XML document follows the basic syntax rules of XML.

A well-formed XML document follows the basic syntax rules of XML. For example, it must have one and only one root element, start and end tags must match, tags must be properly nested, etc. A valid XML document, on the other hand, is a well-formed XML document that also conforms to the rules of a specified XML schema.

XSLT stands for XSL Transformations. It is a language for transforming XML documents into other formats such as HTML, PDF, or other XML documents. An XSLT processor reads the XML document and the XSLT stylesheet, and produces an output document in the format specified by the stylesheet.

XML is used in databases to store and transport data. XML provides a flexible way to represent complex data structures, making it a good choice for storing data that doesn’t fit neatly into a table. Many databases support XML as a data type, allowing you to store XML documents in database columns.

XML continues to be a key technology for data interchange, particularly in enterprise and B2B contexts. While newer technologies like JSON have become popular for web APIs, XML is still widely used in many industries. Its future is likely to be as a specialized tool for certain types of data interchange, rather than as a general-purpose markup language.

Tom is the founder of Triple Dog Dare Media, an Austin, TX-based professional services consultancy that specializes in designing, building, and deploying ecommerce, database, and XML systems. He's spent the last 7 years working in various areas of XML development, including XML document analysis, DTD creation and validation, XML-based taxonomies, and XML-powered content and knowledge management systems.